By Jeremiah Gardner

After a dozen years of writing songs and playing in bands, it was not the Woodstock I had dreamed about.

Rather than rock ‘n’ roll, revelry and youthful excess, tiny Woodstock, Minn., was, and remains, best known for sobriety, and for launching folks on a search for so-called serenity. Surrounded for miles by giant windmills and little else, it is home to a quaint little place for people with substance use disorders. People like me.

I’ll never forget that drive to New Life Treatment Center 18 years ago. It was a Monday, and I had woken up in a hotel – late for work, sick, tired and crying. For reasons I cannot fully explain, that was the day I decided to give up trying so hard and ask for help.

As a friend drove me to Woodstock, he made the prescient comment that my life would never be the same. It seemed a little dramatic at the time, but those words were burned into my mind. Perhaps it was a good expectation to set because, sure enough, my path and trajectory changed profoundly that day.

All these years later, I’m grateful to be able to share with anyone who will listen that recovery from substance use and mental health concerns is real. It happens. Tens of millions of people like me serve as living proof. And not just people like me. Doctors, lawyers, bankers and baristas, singers, sinners and saints. Humans struggle with these issues. All genders, races, ages and socio-economic statuses. And while some people certainly face more barriers than others, recovery and wellness are possible for everyone.

I was fortunate to work for about a dozen years at the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, where I first got the opportunity to spread the dual message that: 1) These are very common health issues, worthy of neither stigmatization nor glorification; and 2) with help, they can be managed and overcome.

In other words, there’s no shame in struggling, and no reason to think we can’t be well. The evidence is in.

But I didn’t always know that.

When I first started having an internal dialogue about my own drinking, I didn’t have a clue where to turn. Left to my own devices, I started adding “Stop Drinking” to my to-do list, as if I could check it off the same as “Get Groceries.”

When “Stop Drinking” never seemed to get checked off the list, I felt like a failure. And when I lied and did stupid, irresponsible things while drinking, I felt like a bad person.

At times, it just felt like who I was – the result of my family culture, as well as the cultures of my first chosen career field, journalism; my dream, rock ‘n’ roll music; and my inherited country, the land of the free spirit. It’s probably true that I didn’t just choose to become a user of mind-altering substances – that I also was bred to become one, and that I was attracted to the sexy glory of it.

But I didn’t count on the problems mounting. I didn’t count on losing control. I didn’t count on developing a substance use disorder involving my brain. I didn’t even know that could happen.

So, as my illness and its symptoms – my behavior – worsened, all I could conclude was that I was weak and somehow willing to betray the values of my innermost self.

Neither shame-laced conclusion was something I wanted to admit.

As a result, I found various ways to deny the problem to myself and others. Like the vast majority of people with substance use and mental health concerns, I avoided and put off getting help. Instead, I’d make trips to the library to see if I could figure things out on my own – maybe learn how to drink normally.

Alone in my thoughts, increasingly discouraged and desperate, I wanted to escape the guilt and shame, and I wanted to feel better. But I also was afraid that if I found a way to quit drinking, I’d lose my identity – not just as a drinker, but as a musician.

What I didn’t have were people in recovery to help or provide a model – no one to say: It’s OK to experience these problems with your health, you’re far from alone, you can get better, and it will be totally worth it – recovery is cool.

I wonder what might have happened if I had known other musicians open about their recovery, or if I had known any happy, successful people open about their recovery. What if I’d seen recovery represented in TV or movies, or taught in school? If substance use and mental health problems, and recovery, weren’t so secret, would I have pursued help sooner?

More importantly: How many people aren’t as lucky as me and never get help at all, suffering through life with their substance use and mental health problems? How many die? And what can we do about it?

That’s where Dissonance comes in. Part of our mission is to smash social stigmas related to mental health and substance use disorders. We do that by producing public events, collecting stories and sharing insights from people whose lived experience demonstrates the reality that these health issues can be managed and overcome – with positive impacts on creativity. The idea is to bring addiction and mental health out of the shadows within the arts community, and shine light on resources and solutions that support wellness and creative work. Ultimately, we want to help and inspire people – both inside and outside the arts community – to take care of themselves and ask for help sooner than later.

With more than a third of households affected by substance use and mental health disorders, it’s safe to say we’re bumping into people every day who might benefit from our messages.

Messages like:

My name is Jeremiah, and I’m a person in long-term recovery. For me, that means I haven’t needed to use alcohol or other drugs in 18 years. It also means I’m able to support friends and family members when they need it. I’m able to have honestly deep and enjoyable discussions - not the drink-addled rantings that passed for philosophical musings in my previous life. I’m an engaged community member. I vote, own a home and pay taxes. I got married and also did the most unlikely thing ever, for me – made a conscious decision to finally have a child – and, as fate would have it, ended up with two!

Recovery has also allowed me to pursue some personal dreams, and start doing smart routine things like going to the doctor and dentist. It has taught me about gratitude, honesty, humility, responsibility, service, authenticity, and the value of listening. Recovery, and the life principles I draw from it, have allowed me to grow up, to see the world anew – and to breathe life into my own life. It has been the most exciting, successful and creatively inspiring period of my life.

Now, if that sounds a little Pollyannaish, let me assure you of two things. First, my recovery is possible only by grace and the gift of others. Second, I’m still flawed as ever.

My ego is still a vast swath of confidence with a raging river of insecurity running through it.

I’m still inclined to perfectionism and procrastination.

I still need to do things to help myself feel decent – like exercise and sleep, even though my instinct is to sit still and stay awake.

I’m still self-absorbed too often, in both obvious ways and subtle ones that I need help seeing.

I’m still streaky most of the time, riding momentum up or down while searching for the secret to steadiness.

And I’m still in the dark about what it all means and why we’re all here.

In short, I’m still human. Only now – in the absence of alcohol and other drugs – I am grateful for the adventure, eyes wide open, soaking it all in. I can see the beauty and spirituality in my, and our, imperfection. I am able to navigate and free to appreciate it all, without habitually hurting myself or others.

It’s a special experience, this life on earth – which is not only the source of all art but a grand work itself. And we’re fortunate to be here, smack dab in the middle.

Even more fortunate to be here together. That’s our ace in the hole – each other. While stigma leads us to believe otherwise, the truth is we are all stumbling. And whether we stumble into a festival in Woodstock, NY, or into a treatment center in Woodstock, MN, we are never alone.

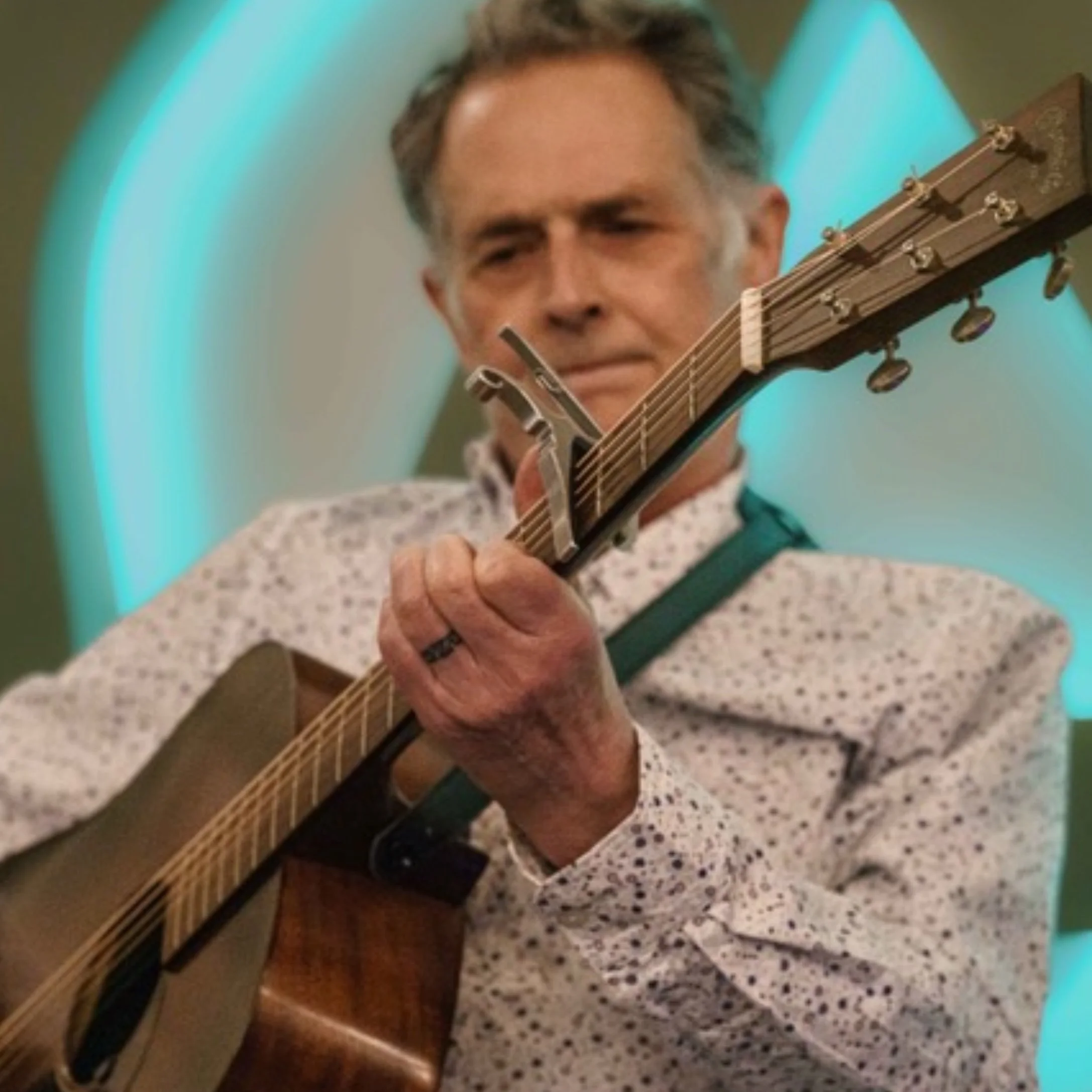

Jeremiah Gardner is a Dissonance Board Member.