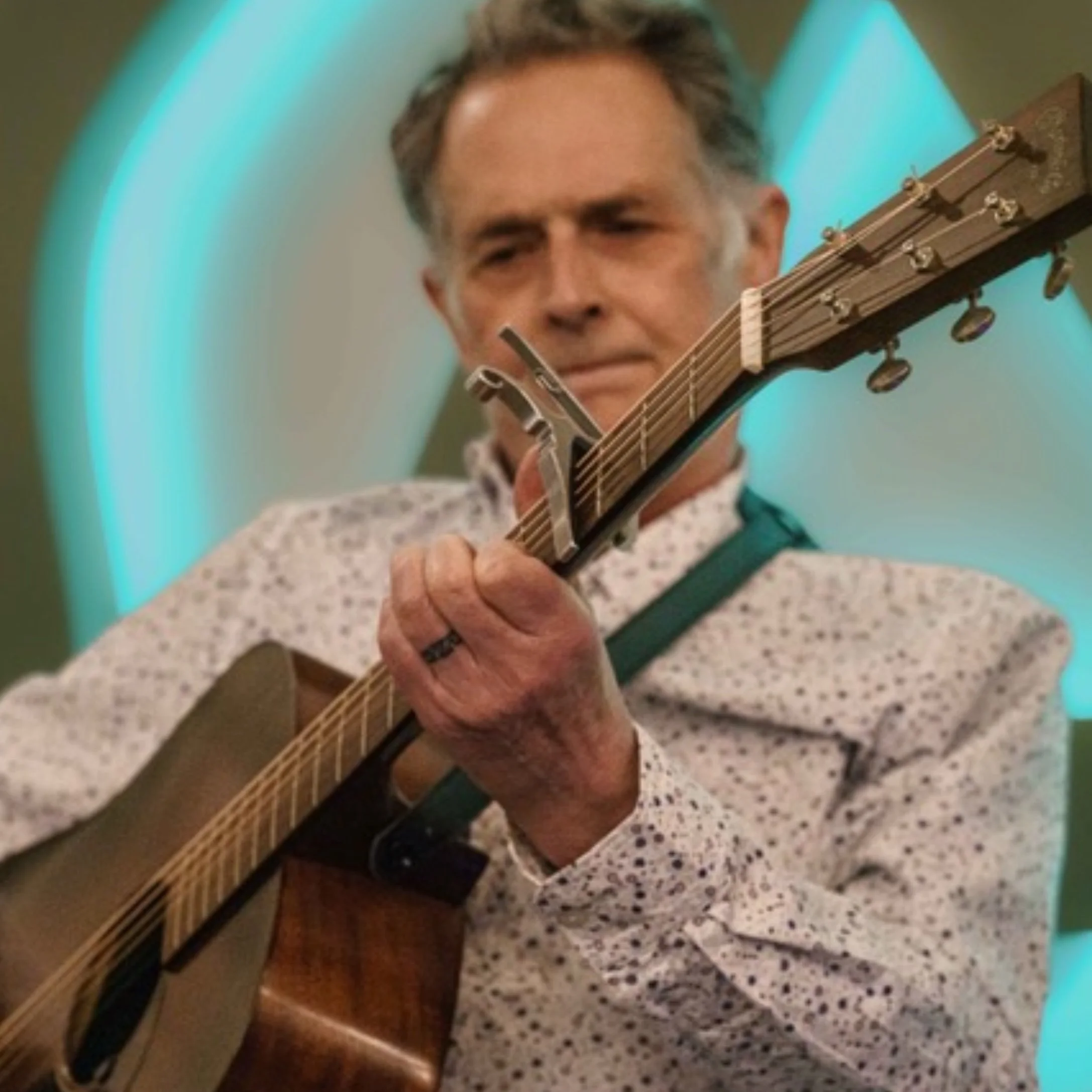

By Phil Circle

It’s a famous story in the lexicon of Phil.

Here's the setup:

It had become well known to my fans that I enjoyed it when they’d bring shots to the stage and place them at my feet. I’d grab them and knock ‘em back while playing guitar one-handed, or, in another display of mock showmanship, pretend I wasn’t watching while bandmates snatched them up. It was a (deadly) bonding experience with my audience. This night was no different.

Here's the pitch:

I’m on stage at Chicago’s Double Door on a Saturday night before a standing-room-only crowd. I look down. There are seven shots of tequila. I shrug my shoulders and reach for one. Then another. People cheer. And the next. They egg me on. Soon, all of the shots have made their way into my addicted body, and I think I’m feeling the warm fuzzies.

And the swing:

The emcee grabs the microphone and gives a brief and flattering rundown of who I am, concluding with, “Ladies and gentleman, Phil Circle!” As the applause ensues, I strut to the mic and let go in grandiose fashion: “Go f*#k yourself! A one, two, three … .” And the band and I kick into our set.

A strike or a hit?

This wasn’t the worst of it. Neither was my 10-minute version of a song that usually goes six. Or my raunchy comments during the show. Or the fact that my drummer quit after the show. The worst part of this evening was the response I received. People loved it. They wanted to see me abuse myself and share my pain with them. They wanted the spectacle.

When I left the stage, I was patted on the back and “treated” to more free drinks. The other bands on the bill all complimented my show. The manager of one of the bands asked me why such a professional group as mine was even sharing a stage with the other bands. I was encouraged to act this way! I was given a free pass to be an ass! I was told in no uncertain terms (that is, I heard it this way) that it’s perfectly fine if I rage in my alcoholism and let it affect my gift … the music. And from that show forward, I used that evening as an example of how great I was. How sick is that? Loaded question.

When I look back at my 30 years of playing music, I see a trend. Every time I got a pat on my back, it went to my head. I guess there’s an “activate ego” button on my upper vertebrae. Once it went to my head, I felt as if I didn’t need to give as much or work as hard. Oh, but I could still drink as hard. When that led to fewer gigs and smaller crowds, I blamed the music business and the public’s poor ear for talent. When this led to resentments, I drank even more. All of this would restart several times until the pats on the back became fewer and turned into skewed glances of concern or scrunched-up wincing faces.

It wasn’t the pancreatitis with its excruciating pain and puking blood that eventually made me quit drinking. It wasn’t the liver disease. It wasn’t the loss of my livelihood. It wasn’t the many ways I was wasting away physically or the potential loss of my best friend, my wife. It wasn’t that my spirit had been squashed and replaced with a debilitating painful despair. The final straw was the difficult realization and admission that I no longer had my art. The thing I loved most in the world, the means by which I shared my genuine love for people, the gift the universe gave me -- it was gone.

When I went to treatment, the first thing my very insightful substance use counselor did was connect me with a spiritual counselor, who also was a guitarist, to discuss grieving. What was I grieving, I asked. The loss of your music, he answered. Soon, my treatment plan included an assignment that scared the crap out of me. I was to play a set of music -- just me, my voice and my guitar -- for the 25 guys in my unit. Sober. No meds. I had only coffee and Skittles® to get me by, and the loving encouragement of a bunch of guys who were strangers to me a couple of weeks prior. It was the first of several performances to my fellows in the treatment center, and slowly, my music came back.

When I returned home, I was asked to play an opening solo set for a woman whose band I had blacked out in front of at my last show, just before leaving for the sober woods up north. She introduced me by telling the story of my previous show, dirt and all. She ended by saying that now she sees a different man. Instead of a cocky strutting rooster, she sees a humble and loving man who just wants to share his gift of music.

“Shit,” I thought, “that’s all I ever wanted to do.”

Afterward, she posted online that I “absolutely kicked ass.” I got teary and felt a strangely different reaction. I wanted to work hard to keep giving something, not taking. I knew this was going to require a lot of hard work, both physically and spiritually.

Today, I keep busy in Buddhism. I keep busy with my guitar and voice. I keep writing. I’m thrilled if three people enjoy something I share. Suddenly, I remember why I started doing this. I love to give. I don’t really care for the so-called rock star image. I don’t want it. I never did. I was immersed in the throes of a disease that pushed for any excuse to stay alive, even at the expense of my life.

And a funny thing has happened at shows. No one asks me if I want a drink. They just tell me how glad they are I quit. And that button on my back when you pat it? It’s turned into an “activate gratitude” button.

Phil Circle has been a working singer, songwriter and guitarist based in Chicago for 30 years. When he’s not writing, recording or performing music, he writes for local music publications and works on the 2nd edition of his book, “The Outback Musicians’ Survival Guide,” a whimsical and informative look at the frontline musician that will include a new chapter, “And Then He Got Sober.” Phil also teaches guitar and voice privately, offering one new piece of advice for aspiring young adult musicians: “The fact that the sex, drugs and booze are typically free is proof they’re potentially bad for you. So, focus on your music.”