By Quillan Roe

I remember a specific day when I was 14 years old. I could not get out of bed. There was no point to getting up, to getting moving, to engaging in the day or my life. It felt completely pointless and overwhelming.

It took until I was 26 or 27 to get help.

After talking with my doctor and filling out mental-health questionnaires, I was diagnosed with dysthymia, which means that I am always feeling a low level of depression, even on my best days.

I forget exactly which one, but dysthymia is caused by a lack of some chemical in my brain, or the inability of my brain to utilize that chemical to its fullest. In other words, it's not that I am lazy or bad or choose to feel this way, or that I am asking for attention; it's that there is a mechanical problem with my brain, and, just like when your car has a mechanical problem, you can take it to an expert and get help with it.

I see a counselor off-and-on, particularly when I'm having a rough patch and need extra help dealing with life. She gives me tools and strategies to work through the various issues that come up.

I'm also on my fourth or fifth medication: it's taken a while to find the right balance between effectiveness and side-effects, but my current meds seem to be doing the trick.

Even with all of this help, I still have a lot of trouble. I frequently get overwhelmed by simple tasks, like doing dishes, rehearsing music, answering emails, maintaining our band’s website, or brushing my teeth. Making a schedule to help with those tasks sometimes helps, and sometimes is overwhelming in itself. I second-, third- and fourth-guess EVERYTHING, down to the smallest decision, to make sure I'm doing it "right." Impostor Syndrome rules my life, and I am pretty paranoid, often assuming that even my closest friends are out to get me. The fact that I've achieved anything in my life, let alone been able to support my family for the past eight years playing music, is simply stunning to me.

With a lot of help from my therapist, I recognize these symptoms for what they are (my therapist calls them "distortions"). But they are still there, and they still need to be dealt with constantly.

All of this is not to ask for pity. I've put off writing this post literally for years. I’ve had no interest in discussing this with folks. I've felt embarrassed and ashamed. But I recognize now that the embarrassment and shame are themselves distortions, and things I need to overcome.

I also recognize that, particularly online, we tend to make our lives look the best we can. And, while we are genuinely happy for our friends, we can also get down on ourselves, thinking our own lives aren't as "great" as the curated version of theirs (I feel this ALL the time).

Hopefully by reading about the reality of my struggles with mental health, others will be encouraged to get the help they need. Since I started getting help, I have never had a day like I did when I was 14, and I count that as a success.

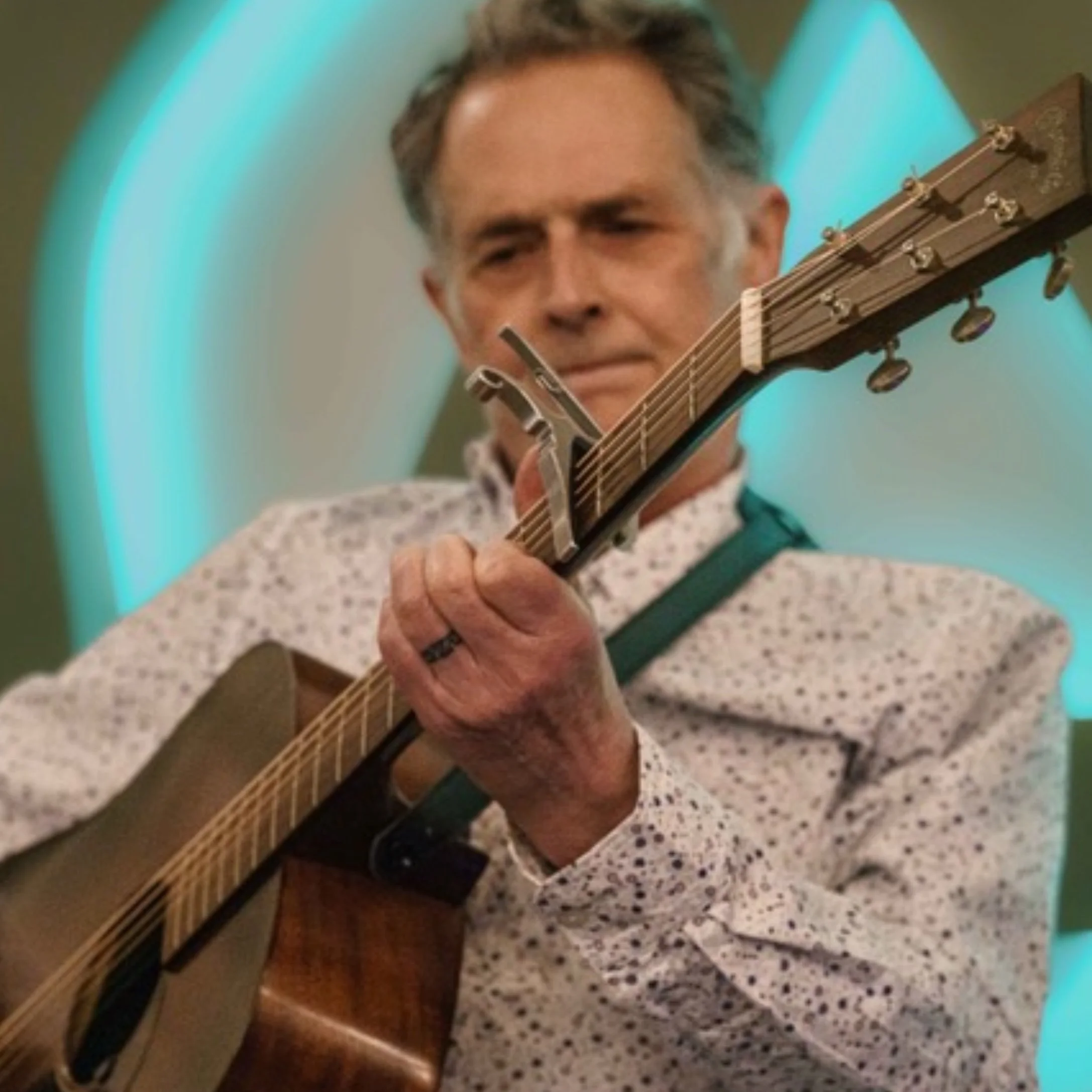

Quillan Roe is co-founder of the Roe Family Singers, a good-time, old-time hillbilly band from the Mississippi-headwaters community of Kirkwood Hollow, Minn. Led by Quillan and his talented wife Kim, the band blends characteristic old-time sound with rock ‘n’ roll urgency and influence. Quillan also leads a congregation with the Blood Washed Band at House of Mercy church in St. Paul, and is involved with a number of other music projects as well. He gratefully celebrated 17 years of sobriety on Jan. 1, 2019.