Part of the First Modern Recovery Advocacy Movement

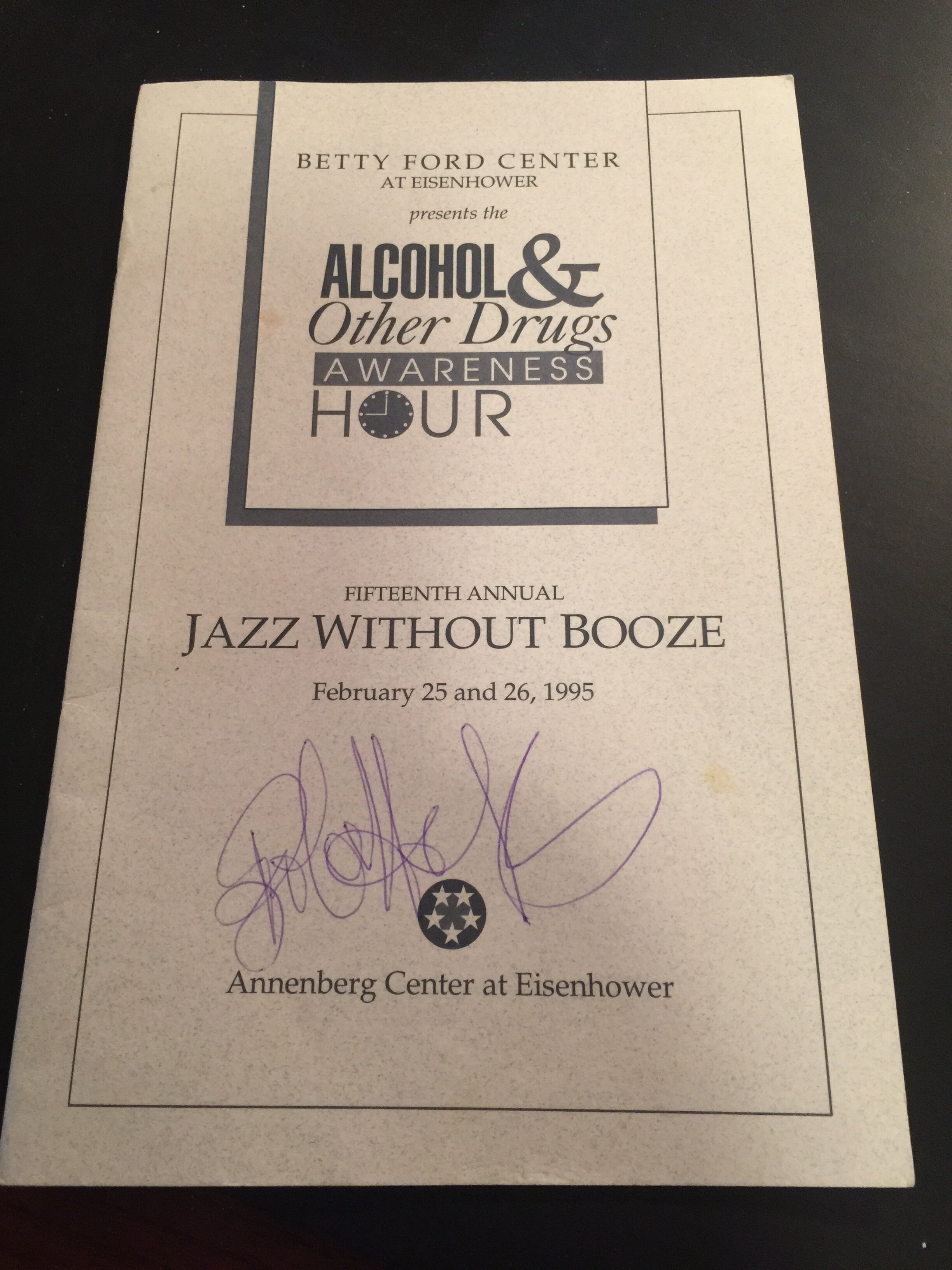

It certainly was an exciting time for recovery advocacy as a vanguard of Americans set out to challenge generations of stigma by putting a positive public face on recovery. In June 1975, the National Council on Alcoholism (NCA) held the first-ever telethon dealing with the disease of alcoholism, and a number of recovering celebrities were involved. Eleven months later, in May 1976, the NCA sponsored Operation Understanding, a televised event in the nation's capital, during which 52 prominent citizens publicly proclaimed their recovery from alcoholism. In June of the same year, FreedomFest '76 was held in Minnesota; it was, and still might be, the largest recovery advocacy event in American history. Just five months after FreedomFest, Dr. Cruse and the Sharbutts launched the Awareness Hour. And, in 17 more short months, Betty Ford would publicly announce that she was in treatment for substance use problems.

"So many things were such a big happening in those days," said Dr. Cruse, who found himself in the middle of a lot of history.

Interestingly, in 1971, Dr. Cruse visited Hazelden in Center City, Minn., looking for ideas to help propel his dream of opening a residential treatment center. Later, after evaluating a county Driver Awareness School in 1976, he got the idea to spread alcohol awareness to the general public, and a short time later, the Awareness Hour was born. Soon, he also was called upon by the Ford family to help with Mrs. Ford's intervention, which he did in 1978. A year later, to the day, Dr. Cruse and Mrs. Ford were both part of the intervention for business and civic leader Leonard Firestone, the former U.S. ambassador to Belgium who sat on the board of Eisenhower with Mrs. Ford and went on to co-found the Betty Ford Center with her in 1982. Dr. Cruse, finally able to see his dream through, became a key member of the leadership team that planned the Betty Ford Center, and he successfully pushed for emulating Hazelden's design and approach, giving him a special place in the annals of the two organizations that are now merged.

When Dr. Cruse resigned as medical director of the Betty Ford Center in 1984, he also left the Awareness Hour, though still attended when he could. Years later, he recognized how special it was to start the Awareness Hour during the first modern recovery advocacy heyday and then to help launch an iconic treatment center.

"I still have a soft, warm spot in my heart for the Awareness Hour. It was such a community undertaking with everybody jumping in, and it was so timely," Dr. Cruse said in 2016. "After I did a couple of interventions, one of them which was Betty's, I do remember driving back to Palm Springs looking up at the big mountains and saying, 'Why, God, do you keep letting me in on these things?' I was certainly fortunate."

When Dr. Cruse moved on to other pursuits, Mr. Sharbutt—who once used his famous voice to read the entire "Big Book" of Alcoholics Anonymous for an audio recording that was distributed to 100 friends of the Betty Ford Center—became the lone emcee for the Awareness Hour. In her biography, Mrs. Ford noted his style.

"Del Sharbutt always greets the audience, and says something like 'Please don't call us reformed alcoholics, you wouldn't talk about a reformed cancer patient, or a reformed heart patient.' Or he may explain that, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Americans drink more alcohol than milk. And another Alcohol Awareness Hour is off and running," she wrote.

In 1978, Mr. Sharbutt's son Jay asked this of his father in an interview published by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: "Some well-known folks like Dick Van Dyke, Ralph Waite of 'The Waltons.' Doc Severinson and Betty Ford have publicly said they're recovered alcoholics and can't drink. Why go public?"

"The whole idea of going on the record is not to take glory for having recovered, but merely to point out that alcoholism is a disease, that you can recover from it, and that no stigma should be attached to alcoholism any more than to cancer, diabetes or heart disease," Mr. Sharbutt responded.

Mrs. Ford agreed, writing in her biography: "That's what all of us, in our separate ways, try to do. Pass along the message. And it is through this sharing, through our own joy in recovery, that we attract others."

Mr. Sharbutt brought that message to Hazelden in Center City on June 13, 1982—four months before the Betty Ford Center opened—when he delivered the keynote address at Hazelden's third annual Alive and Free alumni event. It was yet another connective tissue between the two organizations.