By Kevin O’Connor

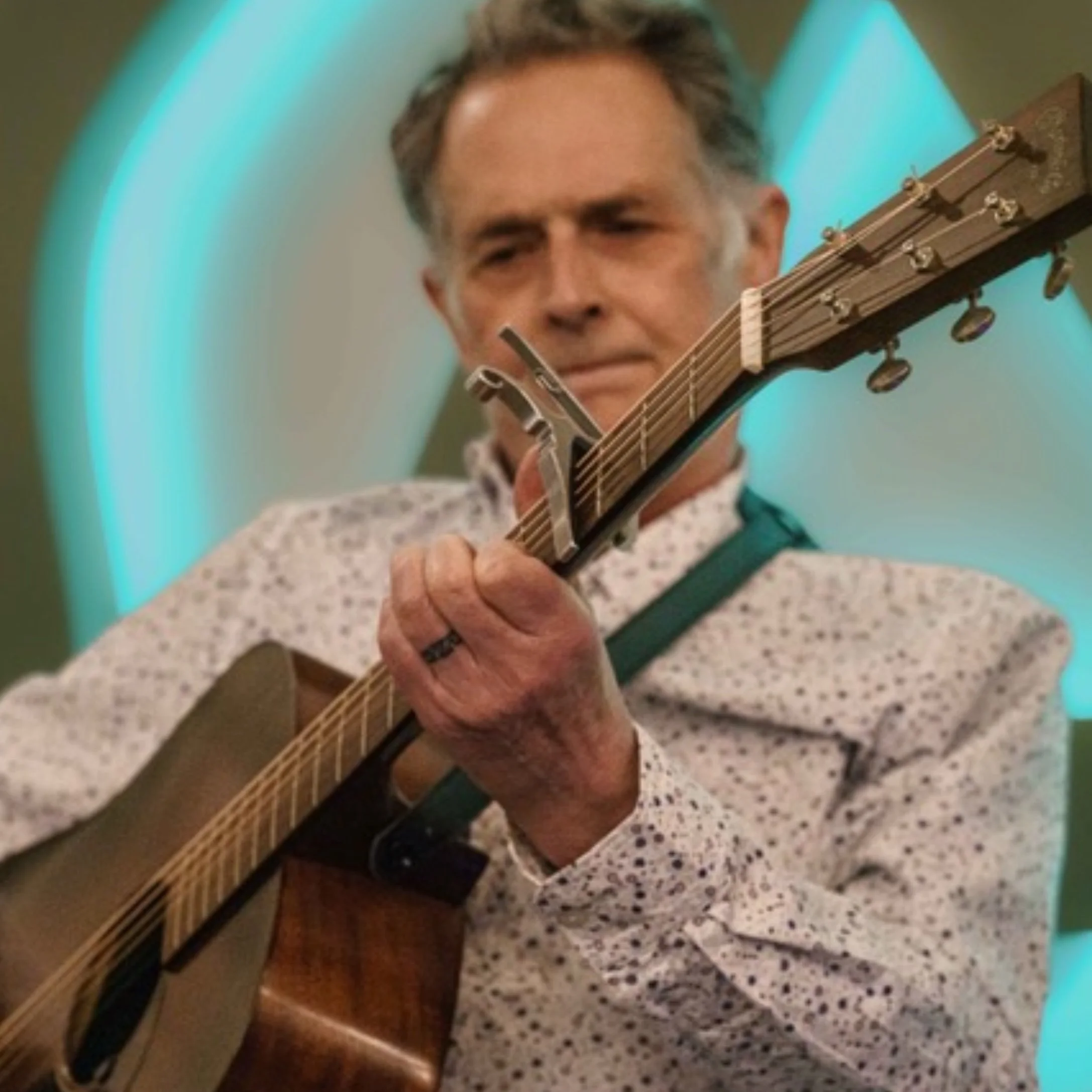

I don’t really identify as an artist. But I am a creative person, albeit a highly reluctant and shy one. I write, paint and plow my way furtively through musical expression. And I create two-wheeled contraptions that are better labeled as art than conveyance. It gives me joy to ride them and even more satisfaction to build them for friends and family.

As a public radio programmer and host, I have devoted my life to supporting the creative endeavors of other artists, mostly musicians. I consider my own talents highly subordinate to theirs and am grateful to be in their company. I suppose there is an art to presenting the art of others, though I don’t expect the MacArthur Foundation grants to be rolling in anytime soon.

But dissonance? Oh my! I can certainly speak to that. In jazz and improvisational music, dissonance is never shunned. In fact, the most revered jazz artists always embraced atonality and what Thelonious Monk described in a famous piece as “Ugly Beauty.”

From the time I could hear notes, I was drawn not to melody or catchy phrasing but to tones of a decidedly more jarring nature. This was a logical response to a noisy, chaotic and traumatic childhood, or so I theorized.

My earliest heroes were people like John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Albert Ayler, and Charlie Parker. Less astonishingly, these and many other geniuses paid dearly for their visitations with addiction, mental illness, or both.

It’s pretty etched in jazz mythology that everybody took heroin so they could play like Charlie Parker. A more apt exploration might be to imagine what he would have sounded like without the junk. He’d have been faster, for sure, which really boggles the mind.

It is these dangerous myths, my connection to art and artists, and my own desire to be well that drew me to the Dissonance community. I had heard about the nonprofit from a colleague and attended its Unhappy Holidays event last year in Minneapolis. The idea of creating safe spaces where creative people with (or without) mental health and addictive issues can share a bit of solidarity and comfort resonated with me instantly.

Freely sharing support—however that manifests itself—among artists who identify as depressed, anxious and/or chemically dependent is nothing short of inspirational. Dissonance is at once focused and inclusive. And, frankly, it serves such a clear need that it’s surprising such communities are so rare.

As for me, I certainly was experiencing dissonance years ago.

Some kids fantasize about being rock or movie stars, practicing in front of a mirror with a hairbrush microphone and broom guitar. Well, at age 10, I was practicing what I anticipated to be my first remarks at an AA meeting. Out loud. Tears and dramatic inflection were well rehearsed by the time I was 12. I wish I were joking, but that’s how hard-wired we were in my family toward a sort of soused pre-destiny. I confess to a slight saturation of after-school specials as well. Who knew Mary from “Little House” could play drunk so well? Or was that Laura?

All too often, it is the creative person who runs toward the fire. For many of us, that impulse is always there, despite varied – and often damaging – results. Finding a balance between following the risky calls to the fire and seeking safety and serenity is a goal I have not yet fully achieved, and precisely why I’m grateful for a community like Dissonance.

Kevin O’Connor is the music director and afternoon host at KBEM-FM, the overnight host at Classical Minnesota Public Radio, and a person in long-term recovery.

Editor’s Note: You are invited to the Warming House, an alcohol-free listening room in South Minneapolis, for a Happy Hour on Thursday, Oct. 26, at 5pm. It’s a chance to learn about the mission and programming of Dissonance, the network of resources and how to get involved, from events to blogs like this one to board service. There will be refreshments, light snacks and music from Theyself. It’s an open invitation to come, connect and unwind a bit.